“It's the sheer exploitation of misery. A fence keeps those who have nothing apart from those who have lost everything." This is how a volunteer who wishes to remain anonymous described the scene outside the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men (Igreja Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Homens Pretos) at Largo do Paissandu square, in downtown São Paulo.

On the night of May 1st, a huge blaze broke out and destroyed a tower block near the church. According to official city data, around 630 people – including adults and children – had been occupying the high-rise since 2003. The Wilton Paes de Almeida Building collapsed and the survivors, many who escaped with nothing but their lives, set out a camp by the church in the surroundings. At least 40 people are still missing.

One week after the tragedy, around 40 families are still camping outside the church, sleeping in tents and waiting for a response by the local, state, and federal governments.

The only concrete action taken by the government so far was a fence set up to keep the ex-residents apart from homeless people who already lived on the streets of the neighbourhood before the fire and have been drawn to the square to find donations that are being made to support the survivors.

Shelters

There have been plans to allocate survivors in shelters. “The local government tried to separate these families by sending them to homeless shelters, but the families wouldn’t take it,” said Ariel de Castro Alves, a lawyer and member of Brazil’s National Human Rights Movement (Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos) and São Paulo State Human Rights Commission (Conselho Estadual de Direitos Humanos). Alves has been helping families to replace the IDs and documents they lost in the fire.

Tarcísio Geraldo Farias, from NGO Ação da Cidadania, is one of the volunteers who is helping the victims. He said that not everyone who lived in the collapsed building is camping at the square.

“There are families who are staying at the relief housing we’ve created at the headquarters of the National Movement of the Homeless People [Movimento Nacional de População em Situação de Rua]. There are families staying at shelters too, people who were desperate and were taken to these places,” he says.

The survivors believe that, if they decide to stay at shelters now, they will eventually be forgotten by city authorities and will never be given a permanent home. Street vendor Adilson da Silva had been living in the occupied building for five years with his wife and four-year-old son and believes he cannot accept that. “We are resisting. This is resistance, those who have stayed here [camping at the square] are resisting,” he claims.

Silva points out that the city government offered a R$1,200 (around US$330) emergency shelter allowance for their first month and a R$400 (US$110) allowance for the following months, up to one year. But he is afraid he will not be able to afford a rent with this allowance. On average, the monthly rent for a 700 square-feet two-bedroom apartment in downtown São Paulo is R$1694 (US$470), according to Imovelweb data from December 2017. Even if the street vendor does find a place, he believes he would end up spending more money commuting, because it would be impossible for the family to find a home in the central area of São Paulo in that price range.

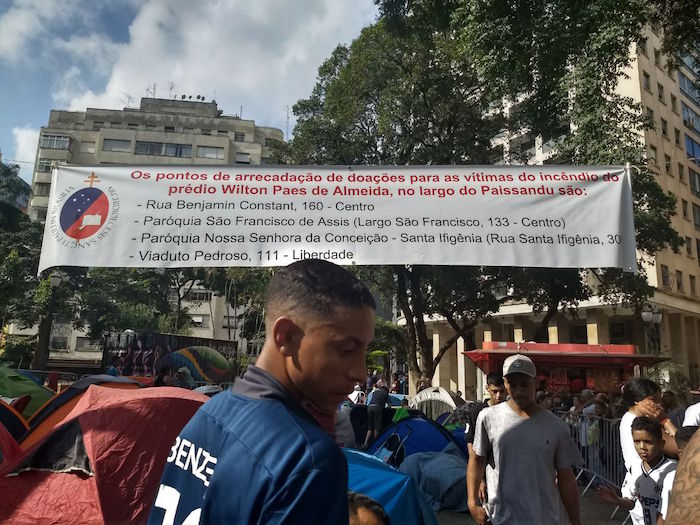

A fence keeps residents apart from homeless people who live in the area. Banner informs where donations should be taken to. | Juliana Gonçalves

“How come a mayor gives me R$400 to rent a house? A sanctimonious moralist like [judge] Sérgio Moro earns a R$4,280 housing allowance, and he owns a house where he lives. And I will get R$400 and then will be left on the street with absolutely nothing,” Silva said, fearing he could be forgotten by the authorities.

Last Friday (4), the ex-residents of the Wilton Paes de Almeida Building released a statement with their demands. Farias points out the most important one: “emergency shelter allowance for one year and, after that, permanent housing service.”

Their other demands are chemical toilets and tents; transparency and access to information about the investigation into the fire; and affordable housing for low-income families on the plot where the high-rise used to be.

Negligence

All the structure outside the scene of the accident was set up by volunteers. They receive and sort out donations, cook, and serve food and water at a makeshift tent.

Clay Albuquerque, a driver who is volunteering outside the church, talks about what he has been seeing over the last few days.

“I’ve been here since the first day as a volunteer, and so far city authorities have not done anything to help. We’ve asked for chemical toilets and they claim they don’t have funds. The city is completely negligent. People with good hearts are helping out a lot, but the city government is doing nothing,” he says.

Lorraine Michelli awaits emergency shelter allowance, but says she will keep resisting. | Juliana Gonçalves

Unlike what the local mainstream media has been reporting, all residents paid rent. Lorraine Michelli, for example, who had been living in the building for five years, used to pay R$200 a month for her place.

The city government released a statement saying it would start paying the emergency shelter allowance to the victims of the fire on Tuesday (8). According to the statement, 116 families signed up last week to start receiving the allowance.

Edited by: Diego Sartorato | Translated by Aline Scátola and reviewed by Pedro Ribeiro Nogueira